We propose a mission concept allowing very high resolution in the

far ultraviolet and ultraviolet, yet not compromising temporal and

spectral resolutions. The compact interferometer system proposed for

SOLARNET is capable of instantaneous imaging through three cophased

telescopes of 35 cm diameter on a one meter baseline feeding a

subtractive double monochromator providing wide field of view and

high spectral resolution. Comprehensive mechanical and optical

realization schemes and image reconstruction scenario have been

developed and are presented. One of the major issue, the validity of

the use of interferometric techniques (recombination principles,

cophasing possibilities), was demonstrated both on a laboratory

representative breadboard and directly on the Sun: feasibility of the

cophasing of two telescopes on extended reference objects.

Furthermore, a complete three telescopes imaging breadboard is now

under realization and will be tested in laboratory this summer and on

the sky this autumn. These progresses in both the modelisation and

laboratory demonstration work truly open the possibility to use and

discover from solar interferometers in Space in the short term, i.e.

in the ESA F2/F3 framework. With a 1 meter baseline or so, a UV

imaging interferometer like SOLARNET will reach a spatial resolution

of 0.02" (20 km in the far UV) and a field-of-view of 40" allowing to

untangle the confining and dissipating mechanisms and processes from

the chromosphere to the corona (the spatial resolution is 40 times

that of any previous experiments in Space). This "small"

interferometer will also provide the first complete test of

interferometric technologies in Space before investing in - much -

larger Astrophysics or Earth Observation missions.

Key words: Sun, solar interferometry, high resolution, solar

imaging and spectrometry.

Back in 1989 we proposed the Solar Ultraviolet Network

(SUN) a 4-telescopes interferometer for imaging (by rotation of the

array as a whole) the fine structure of the Sun and Planets

(Damé et al., 1989). This instrument and the Mission it

belonged to, SIMURIS (Solar Interferometric Mission for Ultrahigh

Resolution Imaging and Spectroscopy), eventually completed a

First Phase of Study in the context of the Space Station in 1991

(Coradini et al., 1991). Studies were pursued up to 1993 when

a smaller version of the interferometer, MUST (Multi-mirror

Ultraviolet Solar Telescope) was considered for the External

Viewing Platform of the Space Station. In parallel, the MUST

interferometric concept (5 telescopes on a circular baseline allowing

snapshot/instantaneous imaging) was also proposed for a satellite

mission (Damé et al., 1993a) with some success.

SOLARNET is the ultimate simplification of the MUST interferometric

imaging concept where the five Ø200 mm telescopes are reduced

to three larger ones of Ø350 mm. This simplifies the

recombination but, also, provides better imaging by an enhanced

coverage of spatial frequencies in the u,v plane. While SOLARNET is

yet considered and recommended by ESA for a future mission on the

Space Station (with a possible priority on the demonstration of

interferometric technologies), it could also be considered as the

heart of a larger ESA Mission in the context of F2/F3.

In support to ESA studies CNES engaged, in 92, Research and

Technologies (R & T) funds for the realization of a

two-telescopes breadboard to demonstrate the heart of the system: the

measurement of an absolute phase and the cophasing control of the

interferometer.

The breadboard was completed in spring 1994 and by September 1994

a complete laboratory demonstration of the cophasing of

two-telescopes on extended objects was achieved (with cophasing

performance better than l/360). During

summer 1995 the breadboard was installed at Meudon Observatory at the

“Grand Sidérostat de Foucault” and the first direct

cophasing on the Sun was made with a phase control of l/140

(Damé, 1996). These cophasing experiments were repeated in

1996 with a better performance: l/240.

Following these successes we can now sustain that we have the recipe

and the cooking skills for the realization of a major instrument for

advances in Solar Physics at the beginning of next century.

In the following, we briefly recall the objectives and concepts of the Solar Imaging Interferometer (SOLARNET), explain the constraints imposed by the measurement of a phase over extended objects, briefly present the past and present laboratory and sky results obtained with this first solar interferometric experiment of cophasing on extended objects like the Sun and Planets (see also our other paper in these proceedings). We conclude with a description of the current design and required resources of SOLARNET as it could be implemented either on the Space Station or on a low cost satellite for the ESA F2/F3 mission using the new PROTEUS platform developed by CNES and AEROSPATIALE.

The relevant minimum observable scale in the solar atmosphere may

be of the order of 10-30 km since smaller scales will probably be

smeared out by plasma micro-instabilities (such as drift waves). This

scale range is comparable to the photon mean free path in the

chromosphere. Slightly larger scales can be expected in the corona

(though gradient across coronal loops may also be a few km).

Altogether this situation is rather fortunate because we have access

to higher resolutions in the far UV than in the visible and X-rays

(multilayer telescopes are limited to resolutions of 1 arcsec or so).

In the UV, the emission lines are generally thin, i.e. not affected

by the optically thick transfer conditions (which prevail in the

visible and near UV lines accessible from ground) and we can expect

to see structures with scales 10 to 30 km. In the visible, thick

transfer in the atmosphere blurs the signature of structures and

nothing smaller than 70-100 km should be observed. This means that

with a single instrument of meter class diameter we have the

appropriate, scientifically justified, spatial resolution for

both the far UV (20 km in the C III line l117.5

nm) and the near UV (60 km in the Ca II K line l396.3

nm).

A breakthrough in high spatial resolution observations (20 km is

40 times more spatial resolution than any previous solar instrument

in Space) should allow to understand in finer physical details

processes like magnetic heating in coronal loops (temperature

profiles, time dependence, spatial localization of heating processes)

but, also, by access to visible wavelengths, the coupling between

turbulent convective eddies and magnetic fields in the photosphere.

Another scientific objective is the plasma heating processes and

thermal inputs of flares and microflares and their fine magnetic

field structures. More details on the scientific objectives can be

found Damé et al. (1993b).

The SOLARNET objectives are indeed to study the Sun and Planets at

very high spatial resolution using spectro-imaging simultaneously in

the far ultraviolet (FUV) and the UV.

High spatial resolution is only one aspect since high spectral

resolution will also be achieved simultaneously from the

photosphere/chromosphere to the transition region and corona (in the

SIMURIS payload, this spectral coverage would be further completed by

larger-field EUV and XUV imaging telescopes at various wavelengths).

phenomena to studying physical processes. Solar

Astrophysics is in a prime position to explain the nature of the

physics underlying observed patterns - rather than just "observing"

the patterns - because the Sun is sufficiently close that basic

physical scales such as density scale height and photon mean free

path are in reach of observation. In angular measure, these are a

million times smaller for other stars; thus, solar physics requires

only a millionth of the baseline needed to resolve comparable

physical processes outside the solar system.

The Sun represents an Astrophysics laboratory of huge interest.

The solar photosphere is the only place where stellar convection can

be observed in detail; the outer atmosphere, pervaded and finely

structured by highly intricate magnetic fields, provides a tremendous

array of plasma processes, offering much to learn to plasma

physicists and astrophysicists alike. The variety of solar research

topics that SOLARNET will revolutionize (MHD configurations:

fluxtubes, canopies, loops; structure and evolution of magnetic

patterns: umbrae, penumbrae, plage, network, grains, fibrils,

spicules, prominences; instabilities and eruptive phenomena: jets,

bullets, explosive events, flares, microflares; radiation

hydrodynamics: granulation, oscillation grains, shocks, extreme limb,

plus probably quite a number of structuring agents and dynamical

processes that aren't known yet, at scales below the few 100 km

resolution) is very large. Nevertheless, they may be grouped together

in a single theme, which is defined as the complex entity constituted

by a magnetically-active star's outer envelope. In the lower

atmosphere, the transition from convective to radiative energy

transport causes detailed structuring of the surface layers

accessible in the visible part of the spectrum; in the structuring

and energy balance of the outer solar atmosphere, a very dynamic

plasma best observed in the ultraviolet down to the soft X-ray

domain, magnetic fields play a dominant role.

The need to achieve high-resolution solar physics with appropriate

diagnostics makes for a specification list of hard-to-meet

requirements for a mission:

Very high spatial resolution. The basic scales at which

processes are observable is set for the solar photosphere by the

photon mean free path, because in optically thick conditions photon

travel lengths set the smallest scale at which the emergent radiation

is coded by structuring in the state parameters. The basic resolution

element one aims for in optically-thick observing therefore measures

a few tenths of kilometers. This applies to the visible and

near-infrared parts of the spectrum, in which the emergent radiation

comes from the photosphere.

For the tenuous outer atmosphere, the situation is very much

different because it contains structures that are optically thin in

many lines, Lya being the major exception.

In optically thin conditions, the emergent radiation (or absorption)

scales with the local extinction and is therefore encoded by

structuring at any length scale. The basic physical resolution is

therefore set by the actual structuring rather then by radiative

transfer. This applies to the ultraviolet and X-ray regimes.

The structuring of the solar atmosphere is dominated by magnetic

fields. These are organized in three basic entities which are

paradigms of solar MHD modeling. At photospheric levels, the field

consists primarily of tiny kilo-Gauss magnetic fluxtubes. They are

clustered into the magnetic network, with intermediate field-free

areas (“cell interiors'”) underlying the magnetic

canopies, into which the outward expanding fluxtubes combine

together in the low chromosphere. At larger height, clustered tube

ensembles join in magnetic loops. These have large lengths but

contain very steep gradients across magnetic field lines. The latter

define the structuring to be resolved in ultraviolet and X-ray

imaging; it has kilometer scales or even smaller sizes. Current

ultraviolet and X-ray imaging and spectrometry just about show that

loops exist, at 1 arcsec or 700 km resolution; to achieve

kilometer-scale resolution thus requires orders of magnitude

improvement.

Multiband observation. The split between the photospheric

regime, observed in the visible, and the outer atmosphere observed at

shorter and longer wavelengths requires simultaneous observing in

different spectral domains. The photosphere and outer atmosphere must

be observed together because of the interplay between them: the

structuring and processes in the nonthermal outer atmosphere are to a

large extent constrained by the configuring impressed by the

convective and oscillatory motion patterns in the photosphere and the

sub-surface layers - where the mass is.

Choosing the ultraviolet over the sub-mm and the X-ray over the

radio domains is obviously dictated by the much larger resolution

obtained per baseline at short wavelengths, the much larger choice of

spectral line diagnostics at short wavelengths, and the much clearer

signatures of temperature and density structuring at shorter

wavelengths.

Selective and tunable spectral imaging. In the ultraviolet,

all emission is concentrated in lines which must be separated (Table

1). In the visible, imaging bands must be sufficiently narrow to

isolate specific layers of the photosphere. Different ultraviolet

emission lines and visible continuum bands supply signals of

differing information content, for example supplying height

resolution in temperature, density and velocity information (Table

2). Diagnostic application requires that the wavelength bands in

which images are obtained can freely be chosen throughout the

spectrum.

Two-dimensional spectrometry. Measuring physical state

parameters (temperature, density, velocity, magnetic field) requires

the use of spectral line diagnostics. In particular, precise Doppler

and magnetic field mapping requires measurement of detailed line

profile shape variations. Such measurement must be achieved with full

two-dimensional resolution.

Photon usage versatility. The large variety of solar

phenomena, structures and processes requires large versatility in

using spectral imaging and imaging spectrometry. Many small

structures evolve very fast, requiring instantaneous imaging; many

have linear geometry, however, so that limited field coverage may

suffice. For other processes, good signal to noise capability is

adamant, requiring longer integration times. Sometimes spatial

resolution must be traded for speed; spectral resolution should also

be an adaptable parameter.

These requirements can only be met by space observation. Of

course, the ultraviolet is only accessible from space; in addition,

in space the isoplanatic patch is essentially infinite, providing

accessibility to off-set reference sources such as the solar limb for

pointing and the disk for cophasing. The SOLARNET mission choice of

new interferometric techniques also furnishes research capabilities

of interest to Solar System science and Astrophysics and,

accordingly, SOLARNET may be seen as a precursor to future

developments, both in the context of understanding astrophysical

processes and in the context of developing space interferometry at

short wavelengths.

|

|||

|

Line |

|

|

Specific Interest |

|

C III |

|

|

Transition zone |

|

S X |

1213 |

|

Corona (density diagnostic) |

|

Lyman a |

|

|

Coronal loops (+ chromospheric studies in the wings) |

|

N V |

|

|

Flares |

|

Si III |

|

|

Density diagnostic |

|

O I |

1305 1306 |

" " |

Chromosphere (but fluorescence with Lyb) |

|

Mg V |

|

|

Active regions & active loops |

|

C II |

1336 |

" |

Filaments & prominences |

|

Fe XII |

|

|

Flares |

|

Fe XXI |

|

|

Flares |

|

O V |

|

|

Flares (impulsive phase 'clock') |

|

Si IV |

|

|

Strong line |

|

O IV |

1405 1407 |

" " |

Transition zone |

|

Si VIII |

1445 |

" |

Plages & activity |

|

Fe X |

|

|

Hot line: coronal Loops |

|

Fe XI |

|

|

" |

|

C IV |

1551 |

" |

Strong line: transition zone |

|

Continuum |

|

|

Temperature minimum fine structure (Bright Points) |

|

He II |

|

|

Sunspots (high chrom. but with coronal contribution) |

|

Mg II k |

2803 |

|

Chromospheric studies (from Tmin to the high chromosphere) |

|

|||

|

Line |

|

|

|

|

Si VIII |

|

|

|

|

S X |

|

|

|

|

C III |

|

|

|

|

Si III |

|

|

|

|

O IV |

|

|

|

Several concrete examples of the high resolution needs are

presented in these proceedings noticeably in the review papers of

Schüssler, Chiuderi, Harrison and Marsch and would be of little

use to duplicate herein. Though let us mention the opened questions

of the threads in prominences (Pojoga et al.; 1998, Mein et

al. 1994; Vial et al., 1989), flare kernels and

microflares (Hudson et al., 1994; Porter et al., 1994),

loops and corona fine structure (Strong et al., 1994; Priest

et al., 1998), polar plumes (Allen et al., 1997),

magnetic canopy (MDI/SOHO), flux tubes, etc.

The paper of Priest et al. (1998) is particularly

instructive. Analyzing the temperature profile of diffuse loops at

the limb (Yohkoh data) they inferred that the loops are not heated

preferentially near the loop base or near the loop summit, but

instead rather uniformly along the loop. In turn this suggests that

the most likely mechanism is turbulent magnetic reconnection in many

current sheets distributed throughout the loop, meaning small scales

of 10-20 km or so.

SOLARNET brings also promising capabilities to non-solar studies requiring high spatial resolution. SOLARNET' photon gathering capacity is modest, but one should note that the Sun is as dim per resolved pixel as any other cool star, specific intensity being the signal measure for image elements rather than irradiance. Following are solar-system scientific objectives of interest for giant and telluric planets, comets and asteroids.

Figure 1. SOLARNET conceptual design (3 telescopes of

Ø350 mm on a 1 meter baseline) shown on the PROTEUS platform.

This version is considered for flight either as a CNES Intermediate

Mission in 2006, as a F2/F3 ESA Mission in 2007/2008, as a NASA MIDEX

Mission, or as a multilateral collaboration, e.g. as an ESA SMART

complemented by a CNES support (PROTEUS Platform).

SOLARNET achieve both high resolution imaging and spectral

filtering. At the distance of Jupiter, the SOLARNET instrument has a

resolution of 60 km in the UV at 120 nm and 240 km in the visible. At

the distance of Saturn, SOLARNET provides maps from the UV to near UV

with resolution in the visible up to 100 mas = 700 km. SOLARNET

resolves Uranus and Neptune in 40 and 25 resolution elements across

their disks in the visible.

Observations performed with SOLARNET will be the UV part of the

global, systematic, long-term multispectral monitoring of Jupiter and

Saturn global magnetospheric dynamics and upper atmospheres

(Prangé, 1992, Zarka, 1992, Prangé and Zarka, 1993 and

Zarka et al., 1996).

For the magnetospheres, the aim is to help understanding the

relative role of internal processes (plasma sources, rapid rotation)

versus external ones (interaction with the solar wind) with respect

to the magnetospheric plasma circulation and the auroral processes.

This will be done by imaging in the FUV and UV spectral ranges the

aurorae (Lyman a, H2 Werner and Lyman

bands, Sn+ and On+ emission lines, auto and hydrocarbon absorption),

of Io (S, O, SO2 in absorption) and of the Io-torus (Sn+ and On+ in

emission), and their correlation to simultaneous observations at

other wavelengths, especially radio.

For the upper atmospheres, still poorly documented and understood,

the major challenge is to determine the balance between the solar

(photon) and auroral (energetic particle) energy input in the upper

atmosphere equilibrium, and their effect on the planetary

thermospheric dynamics, chemistry and energetics (Emerich et

al., 1996, Sommeria et al., 1995). The FUV-UV spectral

range is the most suitable one for remote sensing of the pressure

levels corresponding to the upper atmosphere (Lyman a,

H2 Werner and Lyman bands in emission, hydrocarbons and H2O in

absorption).

For Jupiter's magnetosphere, the objectives include:

Saturn's magnetosphere objectives include:

The dynamics and energetics of Jupiter and Saturn upper

atmospheres is poorly understood. Voyager and IUE observations have

revealed anomalously bright FUV airglow (H, H2) and high

temperatures. This can presumably be associated with the huge energy

input in the polar aurora, particularly for Jupiter (up to 1014 W),

suggesting that the equilibrium of Jupiter and Saturn's thermospheres

is thus presumably controlled by auroral processes, a situation

opposite to the case of the Earth. Very recent high resolution

results from HST confirm the high degree of disturbance of the Jovian

atmosphere from the auroral region (Pallier et al., 1997) down

to the equator (Emerich et al., 1996, Ben Jaffel et

al., 1993) presumably through a complex supersonic thermospheric

circulation pattern (Sommeria et al., 1995). The polar region

of Jupiter and Saturn are also covered by a thin layer of polar hazes

(Connerney et al., 1993) attributed to ion-neutral chemistry

under energetic particle precipitation.

Long-term survey of the planetary UV dayglow would include the following Jupiter and Saturn's atmosphere objectives:

Expected results include:

Multispectral correlations. Multispectral correlations will

be performed with ground-based IR (Jovian aurorae), visible (Io

torus) and radio decameter (>10 MHz, in Nançay)

observations, with Wind and Ulysses data (kilometer to decameter-wave

radio emissions and solar wind parameters) and, hopefully, with a

dedicated radio satellite in the 0.1-10 MHz range.

Observations in the radio range are especially complementary to UV

magnetospheric observations. The emissions occur along (auroral)

magnetic field lines and in Io's torus. They lack spatial resolution

but carry information on the energy and distribution function of

precipitating electrons (keV range), the magnetic field topology, the

evolution of “hot spots” in Io's torus, and the torus

electron content.

Correlations between UV and Radio (and IR) are especially

important for the determination of the type of aurora observed, the

energy budget of precipitations in the auroral regions or Io flux

tube, and for deducing the efficiencies of the various steps leading

to electromagnetic emissions (energy spectrum of accelerated

particles, collisional excitation, joule heating, wave-particle

interactions). At Jupiter, multispectral observations will allow to

study the Io flux tube/ionosphere coupling, the structure,

asymmetries and time variations of Io's plasma torus (in correlation

with other magnetospheric fluctuations), and the transport of plasma

from the torus to the magnetosphere.

Importance of long-term continuous observations.

Previous correlation studies used very discontinuous UV data (IUE

spectra or HST images), together with more continuous radio

(ground-based) observations. Continuous observations will give access

to the variations of magnetospheric (auroral and torus) parameters

with planetary rotation (linked to the asymmetries of the planetary

magnetic field), solar wind interaction, aperiodic storm-like energy

releases, as well as long-term (possibly seasonal) variations.

Continuity in the long-term monitoring of the Jovian and Saturnian

magnetospheres (from Voyager, Ulysses and Galileo, to Cassini,

covering thus >2 solar cycles and 2/3 of Saturn's orbital period)

is especially important for the search of seasonal effects in the

magneto-ionized environments of Jupiter (orbital period = 11.9 years)

and Saturn (= 29.5 years). Remote observations from the Earth's

vicinity can be advantageously combined with in-situ measurements by

Galileo and/or Cassini (or future planetary orbiters), but they will

also provide unique global and continuous informations, not in the

scope or capabilities of in-situ missions. For example, the auroral

activity of Jupiter and Saturn will be studied simultaneously for the

first time, allowing for a comparative study of their magnetospheric

dynamics and of their response to solar wind fluctuations, relative

to that of the Earth's magnetosphere.

Additional objectives. The special magnetospheric activity

of Mercury (substorm-like) and its surface-magnetosphere coupling,

unique in the Solar System could also be studied with SOLARNET. The

need for high spatial resolution in this case has been highlighted in

Prangé (1992), as well as the need for line of sights too

close to the Sun for most of the classical planetary dedicated

designs.

All spatial scales can be observed in the Martian surface and

atmosphere, down to a resolution limit of 40 km in the visible and 10

km in the UV. Structures such as volcanoes or Valle Marineris can be

resolved spatially, and investigated in wavelength bands allowing to

distinguish structures of geological and mineralogical interest.

Also, seasonal surface and surface/atmosphere active processes

effects related to the dust storms and frost covers can be monitored.

Products and ingredients of the photochemical cycle can be observed

at high spatial resolution. This is the case for OH emission at 308

nm or also the 03 UV absorption, which can be observed and monitored

as indicators of stratospheric H20 content.

SOLARNET will contribute to the study of minor bodies in the solar

system by obtaining very high resolution images from the UV to

visible. During a 3 years mission, at least 40 asteroids will be seen

with a size larger than 75 mas. The resolution of SUN in the visible

(80 mas at 400 nm and 25 mas in the UV), will be quite adequate. The

10 larger asteroids with size larger than 250 km (540, 600 and 1016

km for Vesta, Pallas and Ceres) have a diameter at opposition larger

than 200 mas in the asteroid main belt (cf. Table 3). They can be

mapped with a significant resolution in different bands of chemical

and mineralogical interest. Detailed surface features, surface

composition and shapes will be measured.

The irregular shape of asteroids will be measured for those smaller than 200 km, whose stresses have not been overcome by gravity. At the resolution of SOLARNET, asteroids in the main asteroid belts can be resolved down to sizes of 15-70 km. A few small bodies approaching the Earth from the Apollo-Amor family can be resolved down to the kilometer size range. This may be an important tool in the process of identification of the Near Earth Objects. It is also worth insisting on the extreme diversity of asteroids and Kuiper objects (Levasseur-Regourd et al., 1996, Hanner et al., 1994) for which multiple discriminating observations would be extremely valuable. This was confirmed by the recent results of Mathilde flyby (Yeomans et al., 1997; Veverka et al., 1997).

Tunable 10 nm broadband fluxes can be measured for a main belt asteroid using the Double Monochromator of SOLARNET with 1000 counts per 25 mas = 20 km resolution element per 15 minutes of observation. In the filter channel 130-300 nm, the counts will be 20 times more (10000 cts in 15 minutes), allowing high signal to noise mapping. The ultraviolet allows investigation of the OH 306.4 nm and the Lyman Alpha 121.6 nm emission from dormant comets with remaining activity.

In cometary research, major information will come from rendezvous

missions to individual comets such as Wirtanen that Rosetta will

visit in 2011. In 10 years many scientific topics of interest can be

addressed. Although 3 comets have been flown by (Giacobini-Zinner,

Halley, and Grigg-Skjellerup), and 3 others extensively observed

recently (Shoemaker-Levy 9, Yakutake, Hale-Bopp), no information is

available on the densities, composition and structure of cometari

nuclei. Coarse information on the nucleus shape would provide clues

to the aggregation processes and tensile strengths of a significant

variety of nuclei. For understanding the formation of coma jets, dust

and plasma tails and meteoroid streams, high angular resolution is

required. Observations of many comets allows to gather data on

several classes of comets. For the nearby ones, the nucleus will be

resolved down to kilometer sizes (20 km at distance 1 AU from Earth).

The fragmentation of comets approaching from the Sun can also be

observed. By selecting bands of mineralogical or chemical spectral

signatures, the surface distribution can be derived for the larger

comet nuclei. Also, difference in centroid positions of comet nuclei

at different wavelengths can be measured with a sub-kilometer

accuracy on nuclei brighter than 14 magnitude. In association with

photometric rotational modulation, this would allow coarse surface

mapping.

The brightest emission lines of the daughter products of water (H, OH and O) are in the UV. SOLARNET can observe these products near the nucleus. The structure of jets of dust and parent molecules can be followed down to the nucleus, and the activity distribution can be mapped. These can be compared to the highest resolution images that can be obtained in the UV. The inner coma has a very complicated spatial distribution. Gas and dust leave the nucleus both by general diffusion and in jets. The dust can be distinguished from the gas by taking images at wavelengths that do not correspond to the gas fluorescent bands. These allow measuring the spatial density of the dust and the size distribution as a function of distance from the nucleus in the jet and non-jet regions. The coma gas leaves the nuclear region at 0.5 km/s. Gas molecules are dissociated into daughter products H, D, OH, C2, C3, CO, S2, SO, CO2, CN, C, S, CS. The different Swan bands of the hydrocarbons can be selected for imaging with SOLARNET. Cometary emission features of interest include for instance OH 306 nm and Lyman Alpha 120 nm (e.g. for comet Bradfield with respective flux 200 kR and 50 kR, Feldman 1982), CS 257.6 nm, CO2+ 289 nm and CN 388 nm. The variation of their fluxes and distribution can be measured as a function of heliocentric distance. Dust is also a source of gas by evaporation of their constitutive "CHON". Recent observations of Hale-Bopp have shown that looking at bright comets allow to discover near the nuclei, new cometary molecules. With its high resolution SOLARNET has certainly a large discovery potential.

The study of the composition of gas and dust emitted by the

cometary nucleus will allow to characterize the nucleus emission

rate, dynamics and surface distribution. Such studies are feasible as

a function of heliocentric distance for different categories of

comets. On the average, 30 comets are discovered or recovered on each

year; besides, some comets (e.g. Encke) are permanently observable.

The narrow band imaging capabilities of SOLARNET allow to build a

data base on the diversity of the inner coma. It would also provide

unique information on the composition of the ices and dust particles

on the nucleus surface. Finally, it could give some hints about the

shape, activity, origin and evolution of the cometary nuclei.

|

||||

|

|

Name |

Diameter (km) |

half-axis (ua) |

Diameter (mas) |

|

|

|

|

|

If the need for high spatial and spectral resolutions is commonly agreed, the question left is: why an interferometer and not a single-dish large telescope? The first answer is that the required measurement needs exceed conventional instrumentation possibilities. A 1 m telescope diffraction-limited in the far UV is, in practice, exceedingly difficult to construct. And, even assuming that such a perfect 1 m telescope could be built for the far UV, it would be more costly and difficult to control and assemble than an interferometer.

In fact, the Michelson interferometric approach represents significant advantages over diffraction-limited large telescope imaging and the "natural" choice for high resolution is the interferometer for several reasons:

Figure 2. The evident size, mass, alignment control...

advantages of an interferometer of 1 m over a monolithic telescope of

the same diameter.

Figure 3. Comparison of Modulation Transfer Functions (MTF) between a monolithic telescope of 1 meter diameter and an imaging interferometer of the type of SOLARNET with 3 Ø350 mm telescopes on a circular baseline of 1 meter or so. One can notice that SOLARNET has a response at low and high spatial frequencies comparable to the monolithic telescope. The monolithic telescope is superior only in the medium frequencies range and, even in this case (an even if deeps are as low as 7% of the peak), ALL THE SPATIAL FREQUENCIES ARE COVERED by SOLARNET. This unusual, excellent, instantaneous spatial frequencies coverage, makes that , alike a monolithic telescope, SOLARNET will directly provide a 2D image at high resolution in only one single exposure. No need to rotate or rearrange the array, all spatial frequencies being present at once. And, by a simple, direct, deconvolution of this recorded image/interferogram, will the image of the object be recovered.

Altogether, the modest baseline required to obtain major scientific results and the simplified control of an imaging interferometer (which doesn't need an absolute metrology like complex astrometric missions) result in very reasonable cost and mass which open solar (and planetary) interferometry programs to the medium size satellites programs - like the CNES Intermediate Missions on the PROTEUS Platform - or to the limited accommodation capabilities of the International Space Station. SOLARNET, completed with XUV telescopes and larger field instruments, is the baseline of the Reduced SIMURIS Payload adapted to small platforms and satellites (cf. Table 4). XUV spectrometers and solar irradiance monitoring instruments could also be envisaged for completeness as a Solar Observatory. For the Space Station, SOLARNET alone could be envisaged with both scientific and technical objectives (demonstration of a complete interferometric system in Space).

Assuming that we are capable of controlling to a certain extent

the OPD (and the pointing) between the telescopes of the array, we

can register the interferograms (images on which are superimposed the

fringes) and reconstruct the high resolution images. Though, the

method has to be specific since, when the finite size of the

individual telescopes is accounted for, the SOLARNET instrument

samples a full range of spatial frequencies ranging from zero up to

the maximum baseline of 1 m. This completeness is unusual in

conventional interferometry and has more in common with the Fourier

plane coverage of the Multi-Mirror Telescope (MMT). It means that the

imaging capabilities of the instrument are excellent. While

these spatial frequencies are potentially accessible, there are a

number of different schemes for measuring them since measurement of

the fringes is possible in both image or pupil planes. In the image

plane, it is necessary to sample the fringes for a given pair of

telescopes for all independent positions in the image (every

half-Airy disk in practice), while in the pupil plane the equivalent

scheme is to measure fringes for a pair of telescopes for a number of

different spatial offsets or shears between the pupils. In

radio-astronomy, the image plane scheme is used for making images of

objects larger than the Airy disk of the elements of an

interferometric array, each image plane point being sampled

sequentially. However, to image a FOV of 40 x 40 arcsec2

would require thousands of separate fringe measurements for each pair

of telescopes. Clearly, then, a superior method is to place all

these fringes on one detector at once. We then require to

interfere light from all telescopes on a detector covering a FOV of

40 x 40 arcsec2 with a spatial sampling of 12 mas (to achieve

diffraction-limit - 24 mas - of the 1 m array at Lyman a).

The image obtained on the detector instantaneously is the true

object convoluted with the instantaneous point spread function of the

instrument (plus photon noise, etc.). But this direct image

can be restored by inverse methods techniques as we will show.

Since the cophasing will not to be perfect, residual independent

errors will impede the possible quality of the image reconstruction.

Nevertheless, results of compact arrays are far superior than diluted

ones to reconstruct images in these conditions because they allow

complex structures and extended FOVs. This was confirmed and studied

independently by Cornwell et al. (1993, the 'homogeneous'

array concept) and our studies (Damé and Cornwell, 1992,

Damé, 1993, 1994). Millimetric arrays (e.g. like the MMA

project) which are sensitive to phase errors and aiming at extended

FOV are also oriented towards circular and compact array

configurations.

Extensive simulations have been carried for the SUN and MUST

interferometers to establish that excellent images can be obtained

from compact optical arrays despite errors in visibility (contrast)

data, caused by residual beams' mispointing and residual phase errors

between beams. The results are, naturally, very similar for SOLARNET

and, so, please refer to Damé (199', 1993) for illustration of

the influence of flux level, phase and pointing errors on image

reconstruction. These simulations indicate, in particular, that image

dynamics is directly linked to the flux level (N ph/s/pixel) and more

or less limited to , and that when phase errors are ”

l/6 (10° phase error) and pointing

errors are ” 20 mas, reconstructed images are

diffraction-limited to the resolution of the array (dynamical range

is about 400). Though, it is certainly worth to achieve the best

cophasing since the higher dynamical ranges (> 1000 - when flux is

available) are not accessible without nearly perfect cophasing.

However, and even if these simulations are nice and instructive,

it is worthwhile to give a direct "taste" of the imaging capabilities

of an interferometer. For this we choose a "common" object, like a

cat, and submit it to imaging by one of the SOLARNET telescopes alone

(Ø350 mm), a monolithic telescope of 1 m, and the SOLARNET

interferometer of 3 x Ø350 mm telescopes on a 1 m or so

circular baseline. The results are straightforward (cf. Fig. 4) and

show - let us call a cat a cat... - that a compact interferometer of

the type of SOLARNET is strictly equivalent to a monolithic telescope

when phased (and for the same photon gathering: this implies a factor

2 more for the exposure time). Note also that if the monolithic

telescope was not processed (proper deconvolution), then its spatial

resolution would be inferior to the one of the interferometer!

Finally, one should also notice the significant improvement in the

geometry restitution of structures brought by the factor 3 (9 pixels

averaged) between the SOLARNET array and a single Ø350 mm

telescope (cf. the eyes of the cat for example).

Figure 4. Illustration of a simple deconvolution with SOLARNET and comparison with a "small" telescope of Ø350 mm and a "large" of 1 m. From the reference image (Top left) we obtain (2nd line) the image of the "small" telescope (left) and its deconvolution (right); the one of the "large" telescope and its deconvolution (Center) and (Bottom) the image given by SOLARNET and its direct deconvolution (divided by the optical transfer function). Notice the absence of differences between SOLARNET and the large monolithic telescope and the meaning of a factor 3 in resolution between the small telescope and SOLARNET (cf. the "cat's eye" identification).

In practice, this shows that the exceptional - 'compact' - u,v

plane coverage of SOLARNET, and its real-time metrology and

compensation schemes of the pointing and phase errors, allow imaging

capabilities of extended and complex objects similar to those of a

single-dish, monolithic, telescope.

To study the ultimate fine structure of the Sun, a solar

interferometer needs to image an extended field-of-view (FOV) covered

with complex structures. And, since many structures of interest are

evolving rapidly (in a few seconds or even less), this imaging cannot

be achieved by classical long-baseline interferometry techniques

where fringes' visibilities are measured sequentially.

These constraints (FOV and time resolution) prompt to design an

interferometer with instantaneous imaging capability i.e., first, to

the choice of a compact array. By compact is meant that the spatial

frequency coverage of the array is comparable to a single dish

telescope in one fundamental aspect: complete coverage of spatial

frequencies, i.e. there are no zeroes in the modulation transfer

function of the array. Image restoration is, in this case, as we have

just seen, based on a direct deconvolution. A central issue for

interferometric imaging is, therefore, a proper (i.e. compact)

configuration of the array.

The other important requirement is to control the residual optical

path delays between the different telescopes to a fraction of a

wavelength, i.e. to cophase the interferometer. This allows

all the recorded fringes to be used instantaneously, since not

affected by a significant phase problem (thus allowing a robust image

reconstruction approach). The consequence of importance brought by

this cophased approach is that, permanently, we have the insurance of

a near perfect wavefront (stable transfer function), the telescopes

of the array being controlled to their optimum phase position.

The major conceptual choice of our interferometric approach is to

cophase the array. By "cophase" we mean real-time control of the

phase differences between the telescopes, i.e. constant monitoring of

the equality of the optical path-lengths traveled by the different

beams. The result of this cophasing is that the transfer function of

the system is stable. Cophasing has a sound justification since only

cophased arrays can integrate light, i.e. benefit from long exposures

and, thus, from a better signal to noise ratio. The measurement of an

absolute phase on an extended object is not straightforward and we

will first recall some basic notions of coherence.

In our approach of cophasing, the fringes formed in the reference interferometer are obtained by superimposing the pupils. We have direct interferences point-by-point on the pupil and, in each case, the baseline is exactly the same. This is a Michelson case (not a Fizeau case which is obtained when an angle is introduced between the two beams during the superimposition).

Figure 5. Assuming a large spectral bandpass for the source

(300 nm or so at FWHM), the resulting coherence length is short (~

2µm) resulting in 5 major fringes on an optical path of ± 2

µm.

On the contrary to a point source (e.g. a simple star) for which the mutual coherence function (i.e. the fringe pattern as a function of time or, in practice, as a function of the position of a delay-line) is simply the result of the integral over the spectrum (cf. Fig. 5), when the source is extended and with a large spectral bandwidth, spatial effects are added to the temporal ones; this is the general coherence case for the computation of the mutual coherence function where we integrate the source emission spectrum E(x,n) over the frequency domain and the source extension:

where n is the frequency and

t the time delay (expressed in seconds).

Other notations are explained in Damé (1994).

We have evaluated this triple integral for different source

extension z (from 0.15" to 0.6") using the

measured source spectrum of our laboratory source (Dl

Å 300 nm). 0.6" is the classical spatial resolution

(1.22l/D) of a 350 mm telescope at

l800 nm while 0.4" is about the spatial

resolution (l/B) of the interbaseline on

which the contrast is measured (525 mm), i.e. the value at which the

contrast becomes zero. As can be seen from Fig. 5, 0.15" and 0.3",

the two first values, are perfectly acceptable source' sizes since

the fringe contrast in that case is 61% and 22% while 0.35", 0.45" or

0.6", the three other values of the source used in this simulation,

are harder to use, not so because of the value of the contrast, than

because of the required algorithm to localize the central fringe

without ambiguity (the central fringe may not be the most important

one and it can even be negative). Note that the coherent fringes are

present on only ± 2 µm (coherence length of ~ 2

µm).

Figure 6. Fringe visibility as a function of the path delay (in

µm) when the source size varies from 0.15 to 0.6". For reference

sources' sizes less than the spatial resolution of the

interferometer, the contrast of the central fringe can be very good:

“ 60%.

Because of the limited baseline (525 mm) between nearby telescopes

(Ø350 mm), the eventual complexity of the source has only a

negligible influence on the position of the central fringe which

measurement can therefore be considered absolute. However, when

telescopes are small compared to the baseline (classical stellar

case) this assumption may not be true anymore (see, for example,

Annex 1 of Damé, 1994).

For many years we have developed a flux and phase efficient method

for white light fringe tracking by a double synchronous detection

technique (Damé, 1996, Damé et al., 1997a,

b).

A large spectral range (FWHM of 300 nm) is used to materialize

coherence in reference interferometers working between non-repeated

couples of telescopes of an array (e.g. 6 reference interferometers

for 7 telescopes in an array). Because of the large spectral range

only 5 significant fringes or so are present in the coherence domain

(~ ± 2 µm), and with amplitude differences large enough for

an easy identification of the central fringe for which the Optical

Path Delay (OPD) nulling is effective (cf. Fig. 5).

The acquisition of interference fringes and the cophasing of an

array are rather straightforward. Light is cut off the recombined

beams either on a reference object (a reference star in the field) or

on the object on a large, unused if possible, part of the spectrum

(cf. Fig. 7). In the reference interferometers a modulation of the

OPD is performed in one arm of each telescope couple with an

amplitude of l/2 or so. This allows to

perform a synchronous detection at the same frequency than the

modulation to obtain an error signal for the fringe centering (and

phase control, in consequence). This is so because the synchronous

detection is like a derivative where zeros of the function correspond

to maxima. Another synchronous detection at double the frequency of

modulation (a second derivative in some sense) reproduces the fringe

pattern and allows to measure (while the system is already cophased

on a fringe) the amplitude of that fringe. This double synchronous

detection scheme allows, therefore, easily to locate the central

fringe of OPD zero, ensuring the foreseen nulling of the system. This

is explained in some details in our poster paper in these proceedings

(Damé et al.., 1998, hereafter DDKM2); see Fig. 3 of

DDKM2 for an illustration of the double synchronous detection

acquisition and stabilization scheme on the central white-light

fringe.

This method, applicable to the phasing of other interferometers or even large telescopes (like the NGST), has numerous advantages:

Figure 7. To each telescope or pupil segment is associated a

delay line to phase the output beams. After recombination of the

beams, e.g. at the level of an image of the field, a beamsplitter or

field selector is introduced in order to take a reference source or

spectrum to the cophasing system where phases between beams are

measured (in order to control the optical path delays with the delay

lines).

The method is currently demonstrated for two telescopes. Very soon

(this summer) it will be implemented on a 3 telescopes' breadboard to

demonstrate the complete imaging system (cf. DDKM2) and even tested

on sky's objects (the Sun, Planets, stars) at Meudon Observatory this

autumn (such tests on the sky were also carried successfully with the

two telescope breadboard in 95 and 96). This Research and the

Development Program of Space Interferometry Demonstration is

supported by CNES since many years and was awarded recently a three

years study (1998-2000). In this new program, spatialisation of the

reference interferometers is foreseen starting with the three

telescopes reference blocs (by molecular binding) of the SOLARNET

interferometer (Fig. 8). A complete reference system for the

cophasing of 3 telescopes should not exceed the size of a shoe

box.

Let us recall that this measurement of the coherence degree

(contrast) is done by controlling the scanning of a simple delay line

so as to find the coherence zone (± 2 µm) where are the

fringes. The coherence is materialized by a synchronous modulation of

the path delay by another delay line at a reference frequency

n (300 Hz in practice) and with an

amplitude of l/2 or so (obtained by moving

a retroreflector with a controlled piezoelectric), so that when we

are in the coherence zone, the fringe position is shifted and,

consequently, the intensity read on a detector where the fringes

(flat tint in fact) are imaged in pupil plane (diodes of the external

interferometer, cf. DDKM2). Two synchronous detections allow (at the

reference frequency n and at 2n)

to measure the shift (error signal required for the stabilization)

but also its amplitude (so as to determine the best fringe: central

one, highest positive one, etc.). A 20 000 lines of codes

C++ program controls both the acquisition and the stabilization

process since all instruments are linked to the computer by a

GPIB/IEEE card (Frequency Generator, Synchronous Detections, Step

Motors Electronic, Piezoelectric Amplifier, Computer Relays) and

signals acquired (diodes and synchronous detections) monitored

through by an acquisition card. Using the video clock of Windows 3.11

(in the multimedia library), treatment in within a modulation cycle

(faster than 300 Hz) is achieved. Currently, we are undertaking a

major upgrade of the program for use - starting this summer - with

Win32 (NT 4) since preemptive multitasking and multithreading will

bring very significant improvement allowing to control easily a

multi- (5 to 7) telescopes setup.

Following the sky observations carried until last year (cf. Fig. 9

and Damé et al., 1997b) we observed and cophased

fringes on the Sun. Limited performance obtained in these early

experiments (l/150 or so) can be

attributed to the lack of fine pointing (seeing is bad at Meudon,

small fields are not always superimposed, and the small size of the

refractor is sensitive to scintillation when observing stars); by

September the SOLARNET breadboard will be upgraded to three

telescopes and fine pointing (active mirrors) will be

implemented.

Figure 8. SOLARNET 3 telescopes imaging breadboard under

realization at Service d'Aéronomie. The bloc (dash line) shows

the 3 reference interferometers obtained by molecular binding. The

bloc is not to scale and only partly representative (the third

modulation delay line would be in the same plane than the others in a

3D view). The final realization (by mid-99) will be slightly more

compact.

Figure 9. The 2 telescopes breadboard of SOLARNET during

observations at the "Grand Sidérostat de Foucault" (a

Ø800 mm mirror) at the Observatory of Meudon in March

1997.

|

|

|

|

|

(": arcsec) (': arcmin) |

|

|

|

(FUV-UV spectro-imager) |

130 - 300 280 - 400 |

0.025" / 0.002 0.04" / ~ 20 0.06" / 0.001 |

60" x 60" 60" x 60" |

Three Ø35 cm Gregory telescopes on a baseline of 1 m followed by two double monochromators in cascade |

|

|

(Extreme Ultraviolet Telescopes) |

Fe XX/XXIII 13.3 Fe IX/X 17.3 Fe XII/XXI 19.2 Fe XIV 21.1 |

0.6" / ~ 1 |

|

Ø10 cm Ritchey-Chrétien telescope with selectable multilayers |

|

|

(Ultraviolet Camera) HLT |

Lyman a 121.6 C IV 155.0 Continuum 160.0 He II 30.4 |

0.6" / ~ 10 0.6" / ~ 0.8 " 3" / ~ 1.5 |

Full Sun |

Ø10 cm Gregory telescope

with filter wheel (including a FP filter ) Ø10 cm Ritchey-Chrétien telescope (multilayers) |

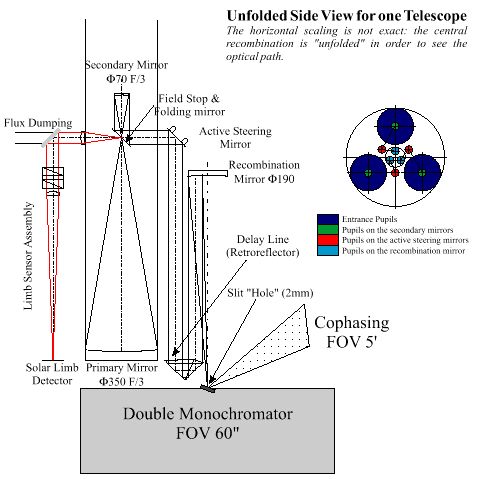

Fig. 10 summarizes the recombination and main optical characteristics of SOLARNET.

SOLARNET is an interferometer made of 3 telescopes of Ø350

mm on a 1 m (950 mm) baseline. A general 3D view is given on Fig. 1

and a conceptual drawing of the optical layout is given in Fig. 10.

The telescopes are Gregory systems, i.e. with an intermediate focus

so as to eliminate most of the useless field-of-view (5 arcmin are

kept for cophasing purpose and for the scientific field-of-view,

60"). The primary of the individual telescope is 350 mm in diameter

opened at f/3 (focal of 1050 mm). The secondary mirror is 7 cm in

diameter (focal of 21 cm). An optical layout of the telescope system

and of the relay to the central recombining mirror is also indicated

on Fig. 10. The recombining mirror (Ø190 and focal 1050 mm)

localizes the light on the entrance slit (a 2 mm hole: 2D slit) of

the scientific instrument (a subtractive double monochromator, SDM)

where most of the field-of-view (5 arcmin minus the 60" that enter

the SDM) is reflected towards the cophasing control system.

Figure 10. Design of SOLARNET (one of the 3 telescopes shown). Note the special use of relays at 30° to fit the recombination on a "small" 190 mm mirror, yet preserving a proper pupil orientation. Fine pointing is achieved on the solar limb taken off from the field stop inside the Gregory. The cophasing (by the delay lines) is monitored from a reference field feeding 3 reference interferometers directly from the entrance slit (2 mm hole) of the scientific instrument. Nothing is lost: 42 arcmin to pointing - 5 arcmin for cophasing - 1 arcmin for the scientific instrument.

Note that because the telescopes are near each other (for

instantaneous image reconstruction high dynamics purpose) that the

central telescope could not be the same size than the telescopes'

primary but had to be smaller. For this reason, the arrangement of

the active relay mirror and delay lines had to be rotated by 30°

(cf. Fig. 10, left: configuration) so that the active mirrors do not

block the light going back from the recombination mirror. By this

original use of the 3D space, the recombination on the smaller

Ø190 mm telescope is possible. It has the further advantage

that an extra mechanism in output of the telescope can be added

easily (as a polarizer for direct magnetic field measurement).

For the focal plane instrument a specific approach had to be

developed since both spectral resolution and spectral bandwidth are

required with the additional constraints that image reconstruction

has to be performed. In practice, since based on Radio Interferometry

methods, our image reconstruction simulations are working on

filtergram type's data, i.e. on non-dispersed narrow bandpasses data.

Adding spectral dispersion would produce extra complexity:

overlapping fringes patterns - and their noise - over the 2D field at

the different free wavelength bands allowed in the output.

Interferometric imaging of complex and extended objects therefore

requires the radio approach of limiting observations to narrow-band

filtergrams. Note that in ground stellar optical interferometry the

problem has not arisen since a slit usually selects a narrow field

corresponding to the natural aperture angle of a speckle size

(turbulence driven choice). In that case, it is a 1D field which gets

to the spectrograph which subsequently disperses it. How to obtain

such narrow bandwidths with grating spectrometers maintaining full

two-dimensional imaging (no dispersion) and also tunability over a

wide wavelength range? By use of a double monochromator in which the

dispersions of the two gratings are subtractive. This concept has

been studied in details up to the tolerance on the chromatic shear

(cf. Damé et al., 1993b). The principle of the

Subtractive Double Monochromator (SDM) is illustrated on Fig. 11,

where the first grating introduces the dispersion and the second one

removes it while in the middle a slit selects, in image plane, the

final spectral bandwidth. This system with two synchronous gratings

provides also stray light protection and easy field selection. While

not necessary for point sources (Astrophysics) this system, capable

of instantaneous 2D-imaging, will also find applications in earth

observation systems and military programs.

The SDM that we propose uses the full potential of the approach by

providing, in addition, simultaneous outputs in cascade, tunable from

the far UV (117 nm) to the visible (400 nm). For this, two SDM are

used in cascade. This is achieved by a Wadsworth mounting of the

first grating. This optical set up (cf. Fig. 12), often used is small

spectrometers, has the advantage that the output beam has a fixed

direction (the exit slit is fixed). In our case, it allows the zero

order reflected by the first grating of the far UV SDM to enter a

second SDM (200 - 400 nm range, cf. Table 5). The input beam to the

second stage is fixed while the far UV SDM scans its spectral range.

By this approach, several channels are observable simultaneously with

a completely free choice of the lines in each of them: they are fully

independent.

Even though it might appear of some complexity (cf. the optical

layout, Fig. 13), this is the only way by which interferometric

imaging can presently be achieved with spectral resolution of 0.01 to

0.1 nm and in different lines simultaneously.

The SDM implementation was studied in details for the SUN and MUST

concepts (Kruizinga et al., 1992, Damé et al.,

1993b) and adapted to SOLARNET.

Figure 12. Illustration of the function of a Wadsworth flat relay mirror for the zero order. Moving the prism (grating) - i.e. selecting lines - does not affect the output direction of the beam (allowing to fed a second double monochromator with the zero order).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FUV: 117 - 200 130 - 300 |

60 x 60 |

|

|

0.04 - 0.1 |

~ 20 |

|

UV: 280 - 400 |

|

|

|

|

(0.001*) |

* This could be achieved with an extra filtering (Fabry-Perot)

Figure 11. Principle of the Double Monochromator of the

SOLARNET Interferometer: optical (a) and spectral (b). The first

grating (G1) disperses the light which is recombined by the second

grating (G2) after a spectral selection, in image plane, done by an

intermediate slit (S).

This simplified version of SOLARNET with only 3 telescopes of

Ø350 mm was first envisaged for the Space Station. This basic

system will allow to test the cophasing techniques and a possible

pointing influence with, if necessary, access to one closure phase.

Additional advantages of this configuration are the reduced number of

optics and the 3-telescopes recombination since larger

interferometers in Space (diluted for Astrophysics needs) will

probably measure phases by recombining beams three by three. This

three by three recombination is not required for Imaging

Interferometers (either solar, planetary, military or dedicated to

earth observations) which will be compact (full spatial frequencies

coverage achieved instantaneously) and, more efficiently, will

recombine directly all beams together to get an extended

field-of-view image.

For interferometric technologies demonstration SOLARNET on a SMART

or on the Space Station will require a primary pointing to half a

degree or so (from the platform for the SMART; from an Hexapod, 6

linear actuators, on the Space Station). Internal fine pointing will

allow to reach the tens of mas required for interferometric

purpose.

A third technology that we will study with SOLARNET is lightweight

telescopes. The three 35 cm telescopes of SOLARNET will represent

only 24 to 30 kg. This is possible since the real-time active

pointing and cophasing, relax the inertial tolerances on the

stability of the telescopes. The active systems will compensate for

the lack of rigidity of the structure.

<

|

Mass |

160 kg (including 20% margin) |

|

Telemetry |

100 kbits/s average |

|

Envelope |

Ø110 x 150 cm3 |

|

Primary pointing accuracy |

0.5° |

|

Primary pointing stability |

0.03°/s |

|

Secondary (active) pointing stability |

< 12 milliarcsec |

|

Internal phase control |

< l/8 (at Lyman a, 120 nm) |

|

Field-of-view |

1.2° (Sun viewing) |

|

Power |

60 watts (peak: 75 watts) |

|

Mission duration |

3 to 6 years |

The technologies tests that SOLARNET will provide are important to many of the currently envisaged mission concepts for high resolution astronomy: cf. the proceedings of the Symposium on Scientific Satellites Achievements and Prospects in Europe, 1996, edited by the AAAF. More than half of the new mission concepts presented at this Symposium were interferometers!

Table 6 summarizes the SOLARNET required resources. Our mass

evaluation includes a 20 % contingency. Telemetry is voluntarily

limited by use of onboard (non-destructive) data compression.

Compression factors of 4 to 6 can be envisaged without losses and,

since progress in this domain happens rapidly, a factor of 10 could

be considered for a flight in 2004-2006.

Figure 13. Configuration of the Subtractive Double

Monochromator (SDM) of SOLARNET. Note, in particular, the sets of

double gratings (G1,G2) and (G3,G4). They rotate synchronously to

compensate for the spectral dispersion. The second SDM is fed by a

flat mirror (W) linked to the first grating (G1) which has the

particularity to send the zero order always in the same direction

(Wadworth's mount).

At the end of this paper, and taking into account the sustained R & D program of this year (3 telescopes imaging breadboard with fine pointing, phase control and image reconstruction on the Sun and Planets), we believe that an imaging interferometer is not at all premature as a very serious candidate for the major instrument of the next ESA solar mission (F2/F3 opportunity). We proved that the major assumption of the overall concept, the cophasing of the array, is feasible and, moreover, that performances to expect are very high. SOLARNET will not only provide breakthrough science with a spatial resolution in the UV 40 times better than anything flown - 0.02" spatial resolution on a 40" FOV - but also at an incredibly low cost because of the compactness of the interferometric concept allowing the use of a standard, industrial, platform like the CNES/AEROSPATIALE PROTEUS one. This should be a clear signal to the solar community that new Physics can come from new technologies readily available, and that a Mission with a 1 meter equivalent telescope could be made around interferometry in the coming years, much earlier - and much easier - that most people would have thought of. Furthermore, this first interferometer in Space will serve as a technology demonstration of interferometric techniques for the future - larger - Space Interferometry Missions or, even, the phasing of the NGST. More details on the instrument and mission scenario, cophasing techniques, image reconstruction algorithms, double monochromator design and spectral performances, and our laboratory and "sky" results are - and will be - available on our Web server:

We would like to mention the contributions of Renée

Prangé, Philippe Zarka and Anny-Chantal Levasseur-Regourd for

the solar system scientific objectives. This work is partly supported

by CNES R & T Grants since 92 and benefited from an ESA TRP

contract for implementing part of the new 3 telescopes breadboard

under realization. We are grateful to MATRA MARCONI SPACE for

financial support in 94 and 95 that allowed to complete the

two-telescopes breadboard and to carry the solar tests at Meudon

Observatory.

Allen, M.J. et al.: 1997, Chromospheric and Coronal Structure of Polar Plumes, Sol. Phys. 174, 367

Ben Jaffel, L., J.T. Clarke, R. Prangé, R.Gladstone, A. Vidal-Madjar, A.: 1993, The Lyman a bulge of Jupiter: Evidence of non-thermal effects, Geophys. Res. Lett. 20, 747-750

Connerney, J. E. P., R. Baron, T. Satoh and T. Owen: 1993, Images of excited H3+ at the foot of the Io flux tube in Jupiter's atmosphere, Science 262, 1035-1038

Coradini, M., Damé, L. et al.: 1991, Solar, Solar System and Stellar Interferometric Mission for Ultrahigh Resolution Imaging and Spectroscopy (SIMURIS), Scientific and Technical Study - Phase I, ESA Report SCI(91)7

Cornwell, T.J., Holdaway, M.A. and Uson, J.M.: 1993, Radio-interferometric imaging of large objects: implications for array design, Astron. Astrophys. 271, 697

Damé, L.: 1998, Low Orbit High Resolution Solar Physics with the Solar Interferometer, Adv. Space Res. 21(1/2), 295-304

Damé, L., Derrien, M., Kozlowski, M. and Merdjane, M.: 1998, Laboratory and Sky Demonstrations of Solar Interferometry Possibilities, these proceedings (DDKM2)

Damé, L.: 1997, A revolutionary concept for high resolution solar physics: solar interferometry, ESA Symposium on Scientific Satellites Achievements and Prospects in Europe, Ed. AAAF, 3.31-3.43

Damé, L., Derrien, M., Kozlowski, M., Merdjane, M. and Clavel, B.: 1997a, Investigation of the low flux servo-controlled limit of a cophased interferometer, CNES International Conference on Space Optics (ICSO'97), Ed. G. Otrio, S2

Damé, L., Hersé, M., Kozlowski, M., Marti, M., Merdjane, M. and Moity, J.: 1997b, Solar interferometry: a revolutionary concept for high resolution solar physics, in Forum THEMIS - Science with THEMIS, Publication de l'Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, Eds. N. Mein and S. Sahal-Bréchot, 187-200

Damé, L.: 1996, The MUST/3T Solar Interferometer: an Interferometric Technologies TestBed on the International Space Station", ESA Symp. on Space Station Utilization, Darmstadt, 30 Sept.-2 Oct. 1996, Ed. T.D. Guyenne, ESA SP-385, 369

Damé, L., Derrien, M., Kozlowski, M. and Ruilier, C.: 1995, Instrumental Prospects in Solar Interferometric Imaging, 27th JOSO Meeting, Benesov, Tcheque Republic, 12-15 November 1995, JOSO Annual Report 1995, 52-59

Damé, L.: 1994, Solar Interferometry: Space and Ground Prospects, in Amplitude and Intensity Spatial Interferometry II, Ed. J.B. Breckinridge, Proc. SPIE-2200, 35-50

Damé, L.: 1993, Actively Cophased Interferometry with SUN/SIMURIS, in Spaceborne Interferometry, Ed. R.D. Reasenberg, Orlando, Proc. SPIE-1947, 161

Damé, L. et al.: 1993a, A Solar Interferometric Mission for Ultrahigh Resolution Imaging and Spectroscopy (SIMURIS), Proposal to ESA Call for the “Next Medium Size Mission - M3”

Damé, L., Marti, M. and Rutten, R.J.: 1993b, Prospects for Very-High-Resolution Solar Physics with the SIMURIS Interferometric Mission, in Scientific Requirements for Future Solar Physics Space Missions, Ed. B. Battrick, ESA SP-1157, 119-144

Damé, L.: 1992, Demonstration and Performances of Real-Time Fringe Tracking: a Step Towards Cophased Interferometers, in Solar Physics and Astrophysics at Interferometric Resolution, Eds. L. Damé and T.D. Guyenne, ESA SP-344, 277

Damé, L. and Cornwell, T.J.: 1992, Interferometric Imaging with the Solar Ultraviolet Network, In ESA Workshop on Solar Plysics and Astrophysics at Interferometric Resolution, Eds. L. Damé and T.D. Guyenne, ESA SP-344, 185

Damé, L. et al.: 1989, A Solar Interferometric Mission for Ultrahigh Resolution Imaging and Spectroscopy (SIMURIS), Proposal to ESA Call for the “Next Medium Size Mission - M2”

Damé, L. and Vakili, F.: 1984, The Ultra Violet Resolution of Large Mirrors via Hartmann Tests and Two Dimensional Fast Fourier Transform Analysis, Optical Eng. 23(6), 759

Emerich, C., Ben Jaffel, L., Clarke, J.T., Prangé, R., Sommeria, J., Gladstone, G.R. and Ballester, G.E.: 1996, Detection of supersonic motions in the upper atmosphere of Jupiter, Science 273, 1085

Hanner, M.S., Hackwell, J.A., Russel, R.W., Lynch, D.K.: 1994, Icarus 112, 490

Hudson, H.S. et al.: 1994, Analysis of Three YOHKOH White-Light Flares, Proc. of Kofu Symposium, Eds. S. Enome and T. Hirayama, NRO Report 360, 397

Kruizinga, B. et al.: 1992, The Solar Ultraviolet Network Subtractive Double Monochromator, ESA Workshop on Solar Physics and Astrophysics at Interferometric Resolution, Eds. L. Damé and T.D. Guyenne, ESA SP-344, 181

Levasseur-Regourd, A.C., Hadamcik, E. and Renard, J.B.: 1996, Astron. Astrophys. 313, 327

Mein, N., Mein, P. and Wijk, J.E.: 1994, Dynamical fine structure of a quiescent filament, Sol. Phys. 151, 75

Pojoga, S., Nikoghossian, A.G. and Mouradian, Z.: 1998, A statistical approach to the investigation of fine structure of solar prominences, Astron. Astrophys. 332, 325

Porter, J. et al.: 1994, Microflaring at the feet of large active regions loops, Proc. of Kofu Symposium, Eds. S. Enome and T. Hirayama, NRO Report 360, 65

Prangé, R.: 1992, Magnetospheres and Atmospheres of Planets, Proceedings Workshop ESASolar Physics and Astrophysics at Interferometric Resolution, Eds. L. Damé and T.D. Guyenne, ESA-SP 344, 131-138

Prangé, R. and Zarka, P.: 1993 (October), J3S: Jupiter and Saturn Systems Survey, response to ESA call for Post-Horizon 2000" mission concepts

Prangé, R., D. Rego and J.C. Gérard: 1995, Lyman a and H2 bands from the giant planets: 2. Effect of the anisotropy of precipitating particles on the interpretation of the 'color ratio' of Jovian aurorae, J. Geophys. Res. 100, 7513

Pallier, L. et al.: 1997, HST spectro-imaging of Jupiter's aurorae with FOC and GHRS, in relation with Galileo in-situ measurements, DPS Meeting 29, 16.08

Priest, E.R., Foley C.R., Heyvaerts, J., Arber, M., Culhane, J.L. and Acton, L.W.: 1998, Ap. J. (submitted)

Rego, D., Prangé, R. and Gérard, J.C.: 1994, Lyman a and H2 bands from the giant planets: 1. Excitation by proton precipitation in the Jovian aurorae, J. Geophys. Res. 99, 17075-17094

Sommeria, J., Ben Jaffel, L. and Prangé, R.: 1995, On the existence of supersonic jet generation in the auroral upper atmosphere of Jupiter, Icarus 199, 2

Veverka, J. et al.: 1997, NEAR's Flyby of 253 Mathilde: Images of a C Asteroid, Science 278, 2109

Vial, J.-C., Rovira, M., Fontenla, J. and Gouttebroze, P.: 1989, Multithread structure as a possible solution for the Lyman ß problem in solar prominences, Proceedings of Colloquium 117, Hvar Observatory Bulletin 13, 47

Yeomans, D.K. et al.: 1997, Estimating the Mass of Asteroid 253 Mathilde from Tracking Data During the NEAR Flyby, Science 278, 2106

Zarka, P. et al: 1996, ISS/J3S: Global Long-Term Multispectral Monitoring of Jupiter and Saturn Magnetospheres, ESA SP-385, 10

Zarka, P.: 1992, The auroral radio emissions from planetary magnetospheres, Adv. Space Res., 12(8), 99-115